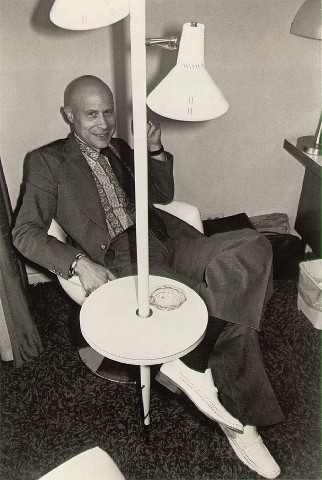

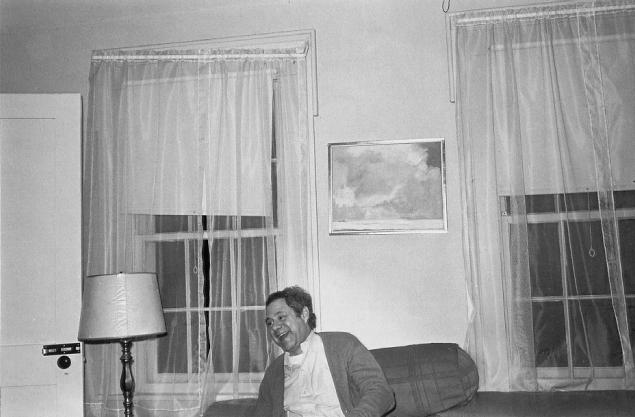

Lee Friedlander is a prominent American photographer famous for his asymmetrical black-and-white images of the social landscape of America. Friedlander started showing an early interest in photography at the age of 14. He attended the Art Centre College of Design to study photography, where he gained a deeper understanding and honed his skills.

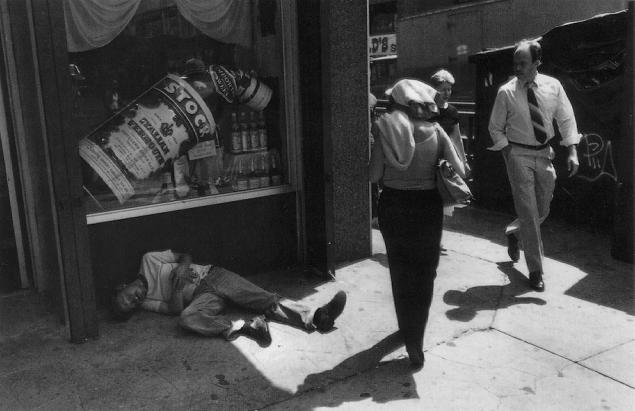

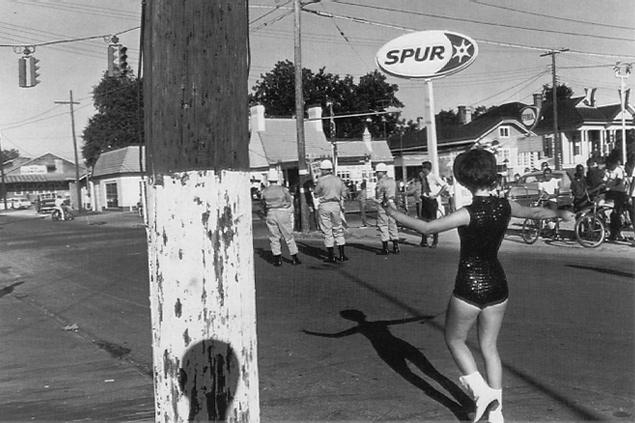

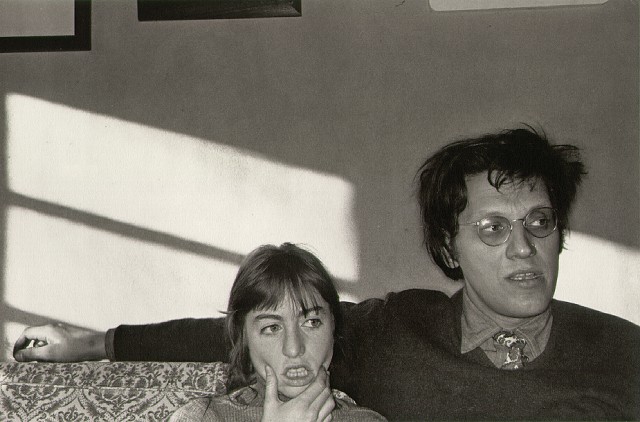

Friedlander’s visual language of urban social landscapes is often imitated. His early works were influenced by Eugène Atget, Robert Frank, and Walker Evans, who inspired him to create candid portraits of people, signs, and reflections in storefront windows. Friedlander’s self-portrait series that started in the 1960s is also recognized as one of his most distinctive works.

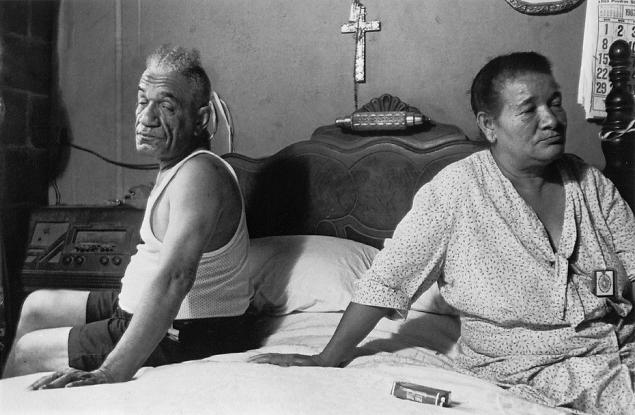

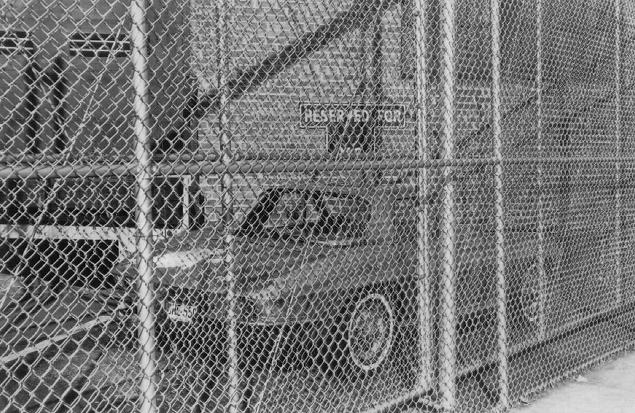

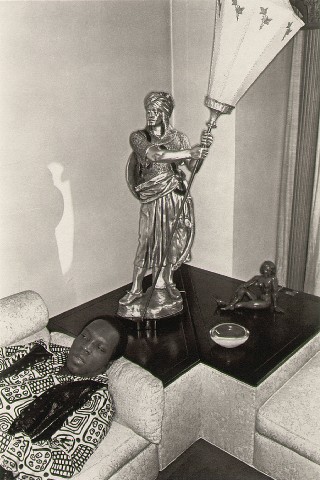

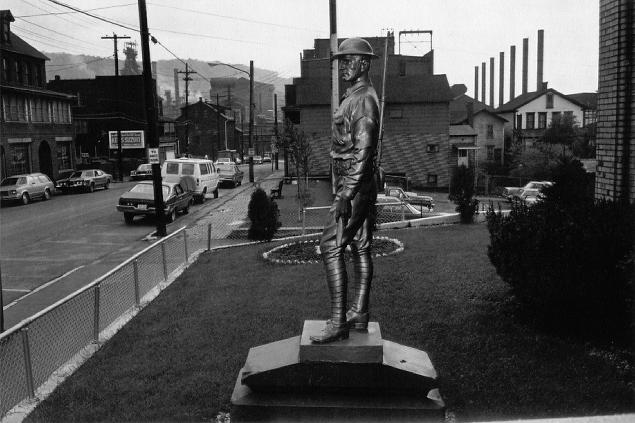

Friedlander combines his own psyche with the ever-changing elements found on the street to convey an authentic urban America experience through his work. His approach provides a photographic accounting narrative that criticizes and questions underlying cultural assumptions yielding mundane yet provocative subject matter. Beyond those who emulate it stylistically or aesthetically, it has become entrenched in contemporary photography history where every subsequent photographer can relate to his way of narrating cities.